Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has stretched the Indian healthcare system to its limits. Strict lockdowns and social distancing protocols have reduced access to regular healthcare services. During these times, tele-consultation has developed itself as an alternate to in-person hospital visit. Between March 2020 and November 2020 online consultation witnessed 300% growth in its user base. It is expected that post pandemic, 20 to 25% of doctor consultations will happen on tele-consultation platforms. It is safe to acknowledge that India’s healthcare ecosystem is on the cusp of a paradigm shift. After remaining resistant to reform for the longest time, the sector is now open to innovation and digital technology-driven medical assistance that became a necessity amid the pandemic. The more the viral strain confined people to their homes, the more virtual care became a reality. Yes, telemedicine is having its moment, and it’s here to stay.

According to the WHO (World Health Organization) telemedicine is:

“The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.”

The key drivers of growth in telemedicine are

Widespread lockdowns and social distancing protocols

Fear of catching the virus

Release of telemedicine guidelines

Increasing internet and smartphone penetration

Increasing provider willingness to use tele-health

Telemedicine might soon become ubiquitous in the healthcare system because of its plethora of benefits. A few of its important advantages are:

It enhances accessibility to healthcare while reducing the time required for it.

The most important benefit of telemedicine is that it saves time, cost, and effort, especially for medically underserved communities, as they need not travel long distances for obtaining consultation and treatment.

Owing to the digital nature of telemedicine, documentation becomes efficient for both patients/caregivers and doctors. This ensures better legal protection for both parties.

Telemedicine provides patient safety, as well as health workers safety especially in situations where there is a risk of contagious infections.

In this paper, we aim to present the policies and implementation model of tele-consultation that the government should adopt to reach closer to achieving its vision of ‘health for all.’ We would be focusing only on the tele-consultation aspect of telemedicine, which is defined as “synchronous or asynchronous consultation using information and communication technology to omit geographical and functional distance.”

We had undertaken a study on the current policies and implementation models of the government and a survey of the current market of tele-consultation. Various stakeholders’ perspectives have been identified as well to incorporate a holistic view in our recommendations.

Stakeholder Analysis

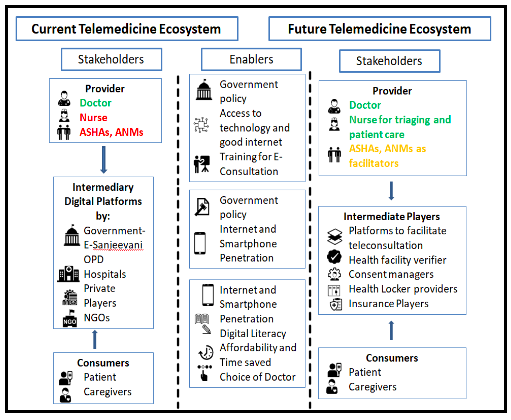

Our scope of work in this paper will involve only tele-consultation. The key stakeholders in this case are Physicians, Nurses, platforms providing telemedicine services and government. As shown in the diagram, the current Telemedicine ecosystem predominantly consists of four key players:

Healthcare providers i.e. RMPs and nurses

Intermediaries facilitating Tele-consultation largely dominated by platforms

Customers which includes patients and care-givers

Government at Centre and State

The Union and state government is the only stakeholder currently involved as regulators and intermediaries of tele-consultation services. The stakeholder analysis will look into the implications of the new policy for two main stakeholders i.e. Healthcare professionals and patients.

Red color indicates absence of role/ defined role,Yellow color indicates assistive (intermediary) role and Green color indicates presence of a defined role

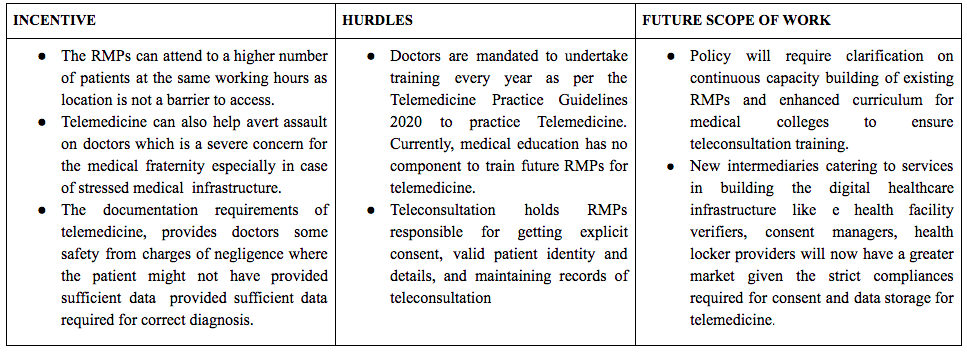

The adoption of the Telemedicine Practice guidelines, 2020 has provided the much needed regulatory framework for the digital healthcare ecosystems. However, the framework also gives rise to certain challenges for each of the stakeholders which are provided in the following table. These challenges and blindspots if solved for soon; will give rise to a much sophisticated future digital healthcare system as shown in the Figure.

RMPs

Nurses

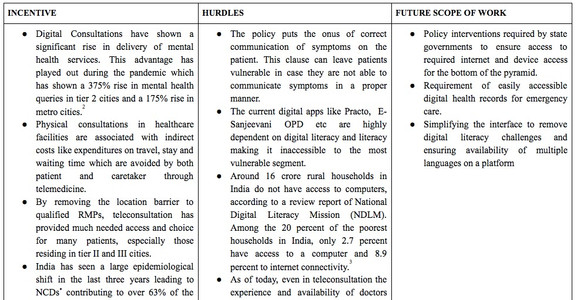

Patients

Issues with Existing Policy Framework

Though the attention towards tele-consultation arose substantially after the onset of COVID-19, some significant steps have already been taken both by the Central Government of India and various state governments towards introducing tele-consultation as a sector. The policies and government initiatives that solve for different issues in setting up tele-consultation are tabulated in the annexure.

However, the policies lack multiple dimensions ranging from vision, feasibility to governance as discussed below.

1. Lack of comprehensive legislative framework

The National Digital Health Ecosystem (NDHE) in India is currently governed by various policies and guidelines, such as National Health Policy, National Digital Health Blueprint, National Digital Health Mission (NDHM), wherein tele-consultation has become an integral element of transforming the health care in India. Furthermore, the practical execution of tele-consultation by health care professionals such as, RMPs and nurses, is governed by separate guidelines, in addition to the other national clinical standards, protocols, policies and procedures.

However, there are no guidelines governing the technology platforms providing tele-consultation services and medical establishments (in case such establishments are also providing tele-consultation services). In addition to the providers of tele-consultation services, there are a host of other service providers in the NDHE associated with the tele-consultation sector which currently has no specific governing framework, such as payment gateways, communication channels, consent managers, etc. In order to avoid conflicts and contradictions between different governing frameworks; to have all aspects of tele-consultation regulated; and to inter-link and interconnect each stakeholder and process involved, a comprehensive legislative framework should be enacted.

Further, it is also paramount to ensure coordination and readiness of the state governments in implementing tele-consultation framework within their states’ healthcare sectors, given that health is a state subject. Currently, we do not have a state specific framework to ensure proper implementation of tele-consultation.

Moreover, the tele-consultation sector is a collaborative action amongst different ministries/departments of the Government of India, State Governments/Union Territories, private sector/civil society organizations. Given the inter-linkages and lack of a single unified existing framework, there is a need for developing proper coordination and delegation framework between the stakeholders responsible for tele-consultation implementation in India.

2. Lack of a unified regulatory authority

The governance framework of NDHM is divided between regulatory and implementation/ operational framework. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology have been entrusted with the responsibility of framing legal and regulatory framework, whereas National Health Authority (NHA) is responsible for the implementation of NDHM and coordination between different stakeholders. Further, the NDHM is only responsible for redressing grievances relating to telemedicine services on its system, and any other grievances shall be redressed by different authorities.

However, the NHA is an interim body for governing the NDHM, including tele-consultation services. In such a complex and interlinked structure, there is a pressing need for designating a single or comprehensive regulatory authority governing the tele-consultation services to ensure clarity of command and ensure smooth functioning of the tele-consultation practices.

3. Lack of practice guidelines for all stakeholders involved in providing teleconsultation services

The service of tele-consultation shall primarily be provided by the medical professionals, such as RMPs and nurses. The Telemedicine Guidelines cover norms and standards of an RMP to consult patients via telemedicine. The Telemedicine Guidelines also envisage tele-consultation between a health worker (such as nurses) and an RMP. To facilitate such tele-consultation, the TeleNursing Guidelines have been issued.

However, there is a lack of practice guidelines for the technology platforms which provide tele-consultation services, through the on boarded RMPs, to its users. The Telemedicine Guidelines do take note of such platforms and provide a few generic guidelines for such technology platforms whilst ensuring that only registered RMPs are providing tele-consultation services to the patients. Further, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a rise in private medical establishments initiating their own tele-consultation portals. However, there are no specific practice guidelines governing such medical establishments or technology platforms providing tele-consultation services to their users.

4. Lack of health data privacy protection framework

Tele-consultation uses information and communication technologies to exchange information between a patient/user and a medical professional for health consultation. The patient’s information and medical reports, along with other personal data, are sensitive personal data or information which should be protected. Currently, such personal data of the patients can be considered as sensitive personal data or information (“SPDI”) under the Information Technology (Reasonable security practices and procedures and sensitive personal data or information) Rules, 2011 (“IT Rules”). The IT Rules mandates a body corporate to meet certain standards regarding the collection, storing, transferring and processing of SPDI. The Information Technology Act, 2000 provides for certain penalties in case of non-compliance of IT Rules.

However, the compliance requirement is only on a corporate body and not on individuals under the current IT framework, contradicting the requirement of Telemedicine Guidelines, 2020 to make the RMPs responsible for data privacy compliance. Currently, there is no specific data protection law in force in India protecting the privacy and security of digital health information.

However, there are two draft bills i.e. Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 and health sector specific Digital Information Security in Healthcare Act (DISHA) which are pending in the Parliament of India. Further, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has issued a Health Data Management Policy as a first step in realizing the NDHM’s guiding principle of “Security and Privacy by Design” for the protection of individuals’/data principal’s personal digital health data privacy. It acts as a guidance document across the NDHE and sets out the minimum standard for data privacy protection that should be followed across the board in order to ensure compliance with relevant and applicable laws, rules and regulations.

Accessibility Issues with the existing Tele-consultation Models

1. Infrastructure Issues

Lack of Adequate internet infrastructure

55% of India’s population does not have access to the internet. There is a huge disparity in internet access between rural and urban areas, only 31% of rural india has internet access as compared to 67% of urban india. According to e-Sanjeevani’s website for a smooth full-motion video consultation experience, internet speed of at least 1Mbps is recommended which could be a barrier for a lot of internet users in rural India. There have been reports of the e-Sanjeevani app not working properly in areas with low internet bandwidth.

Increasing the points of access for rural patients to this tele-consultation service is the top priority. Setting up 1,55,000 Health & Wellness Centres (HWCs) by December 2022 as envisioned by the GoI needs to be ensured. In the meantime, the decision to use Common Services Centres (CSCs) for provision of e-Sanjeevani service is a step in the right direction.

Lack of Doctors

India struggles with shortage of doctors, with a doctor to population ratio of 1:1511 against the WHO norm of 1:1000. Both private and e-sanjeevani oOPD struggles with this shortage which is evident from several complaint by users of long wait time and late or no response by doctors.

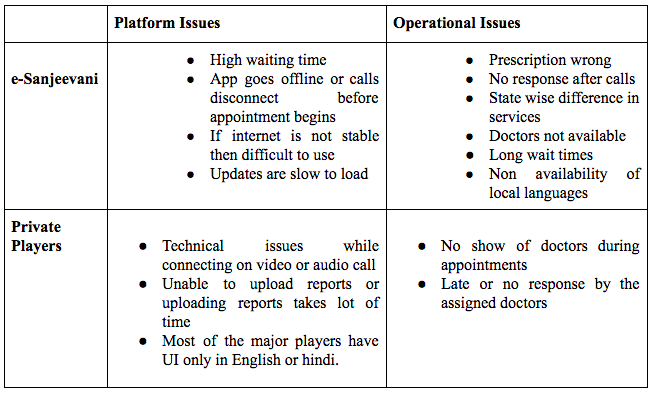

2. Issues with Intermediary platforms

User Experience On e-Sanjeevani and Private Players

The major challenges faced by users on the App include (based on reviews of the App on Google Playstore):

Language Barrier

90% of Indian internet users prefer the local language instead of English. 8 out of 10 largest tele-consultation apps analysed for this paper have their UI in english or in english and hindi. This leaves about 45%* of India’s internet users underserved. GOI’s e-Sanjeevani OPD also has an English UI and without the feature of mapping patients and doctors on the basis of language leading to lower quality of healthcare.

3. Lack of awareness

According to a survey conducted among healthcare students in India in 2020, 43% of the study population reported insufficient knowledge of telemedicine and 52.1% had insufficient knowledge about its application. The study also revealed that only 14.7% of the students were aware of the new telemedicine guidelines. Several other studies have shown similar results indicating a lack of understanding and awareness.

Policy Recommendations to pave the way forward

1. Creation of Apex regulatory body to govern telemedicine ecosystem

An apex body must be created by the MoHFW to govern the telemedicine eco-system (Telemedicine Council of India). The council must comprise doctors, lawyers, and professionals working in the health sector.

The agency must be given autonomy to devise guidelines for tele-consultation stakeholders, run courses for training of RMPs and nurses, oversee quality hand holding to doctors, nurses and allied staff. It would also create an enabling infrastructural and regulatory environment with clearly defined roles, responsibilities, benefits and risks for all stakeholders, including financial reimbursement mechanisms for tele-consulting service delivery. The agency would work on inter-connecting Sub-District Hospital (SDH)/Primary Health Centre (PHC)/Community Health Centre (CHC), district hospital and medical college in every state for providing citizen-centric services.

2. Infrastructure

Using ATM-like kiosks to bridge infrastructural divides across the country.

We know that 70% of India’s population resides in rural areas. The issue of increasing access to teleconsultation especially within rural areas can be solved by making physical infrastructure available in these areas, similar to CSCs. The concept of Health ATMs can facilitate an increase in teleconsultation and other tele-health facilities. For instance, Mumbai based Yolo Health ATMs, HOPS Health ATM, Tech Mahindra Health ATMs provide health check-ups, connect to a doctor and maintain records.

The Health ATMs also provide live video consultation, instant diagnostics, preventive health check-ups, and an option of continued mobile consultation. Moreover, the ATMs offer both online and offline consultancy. Generally, the communication is done over a 1 Mbps bandwidth using cellular network (2G/3G).

Bridging Infrastructural divide using technology

BharatNet is a GoI scheme that envisions connecting all the Gram Panchayats of India with high speed internet for better service delivery to rural India. The work was divided into 3 phases and its first 2 phases have failed to deliver on their objectives. However, in June 2021 the GoI finally entered into a Public Private Partnership (PPP) to fast track the progress of the project. This PPP gives hope to the future success of the national tele-consultation service. In the meantime, the app needs to support video/image transmission on low internet speed and also via SMS/MMS in areas without internet access. A dedicated helpline to allow for offline and asynchronous consultation is also a must.

Roping in foreign doctors to increase accessibility

Under ‘territorial jurisdiction’ of the Telemedicine Practice Guidelines, nothing states that Indian patients cannot access tele-consultation services from doctors who are not Indian residents. Hence, foreign doctors could help in reducing the burden on the current medical system. Doctors from different parts of the world provided tele-consulting services to around 2000+ patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bringing this under an institutional setup would help in expanding the doctors’ networks and to meet the growing demand in the tele-consultation sector, especially e-Sanjeevani portal.

3. Improving user experience using a Digital Health Assistant

Based on the user reviews for both e-Sanjeevani app and apps of private players, it is suggested that a digital health assistant be incorporated in the app of the national tele-consultation service for the following reasons. It would make the use of asynchronous tele-consultation efficient and effective for both the doctors and the patients/caregivers. Also, it would solve for the current technical and logistical challenges faced on the apps like call drops and doctors not being able to show up on the designated time.

The digital health assistant would be programmed with history taking protocols. These protocols can be designed in an easy to follow manner for the patient or the health worker with multiple choices for each question, assisted by multimedia aids to enable better understanding of the symptoms or conditions.

The doctor would receive a document with the prior history and where applicable & possible a note on the physical examination of the patient. This would be represented in natural language for the ease of understanding of the doctor (using AI).

Ayu is a working example of a digital health assistant successfully employed by a not-for-profit organization called Intelehealth in its pilot studies and the above model has been explained on the basis of Ayu.

4. State-level Mapping of Languages

The GoI can decentralize this process such that individual states collaborate with the central agency working on the app directly. States should ideally ensure that for each official language recognized by it, there are at least a few doctors on the app who converse in it as well as read and write in it. The UI/UX of the app also needs to reflect this linguistic diversity. A good starting point for the GoI’s national tele-consultation app, currently e-Sanjeevani, would be to emulate the private players like ‘Jio healthhub’ which has UI in 11 languages and provides an option to choose doctors in local languages as well. Another private player ‘MyUpchar’ provides healthcare information in 5 languages.

5. Building Awareness of Tele-consultation

The vaccination campaign by the Government of India against the polio virus is a stellar example of how awareness can be raised to reach the last mile citizens. Taking cues from this polio-eradication campaign with 100% success rate, roping in influential celebrities as brand ambassadors and rigorously promoting the benefits of teleconsultation through mass media is required at a macro-level.

At a micro-level, frontline workers (FLWs) like anganwadi workers, auxiliary nurse midwives, school teachers and even gram panchayats should be used for raising awareness within smaller communities (villages), with a special focus on the accessibility to and affordability of healthcare that tele-consultation provides. The awareness campaign for tele-consultation can be clubbed with various other current health programs that the FLWs have to manage, as eventually it would translate into better health outcomes and lesser burden for them in the future.

6. Some Government schemes that can aid in implementing tele-consultation

Speedy implementation of National Medical College Network (NMCN) & National Telemedicine Network

Telemedicine in general and tele-consultation in particular is an idea whose time had come even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is reflected from some earlier initiatives of the Government. Under the National Medical College Network (NMCN) scheme, 50 Govt. Medical Colleges are being interlinked for the purpose of tele-education, e-learning and online medical consultation by utilising the connectivity provided by National Knowledge Network (NKN). This initiative, inter alia, provides specialty/super specialty doctors from these medical colleges giving online medical consultation facility to citizens which will be similar to OPD facility through a web-portal. This will help patients from rural and urban areas access doctors and specialists easily even from their home or government hospitals, even remotely.

Similarly, the National Telemedicine Network, can help provide telemedicine services to the remote areas by upgrading existing government healthcare facilities (State, Primary, District Health Centres). Telemedicine nodes across India are being created inter-connecting SDH/PHC/CHC, district hospital and medical college in every state for providing citizen-centric services. While locations for National and Regional Resource Centres have been identified as per NMCN, clarity in implementation of NMCN can help the country move closer to the idea of Tele-consultation in specific and Telemedicine in particular.

In an interview in 2019, Health Secretary, Ms. Preeti Sudan, noted that states such as Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh were being supported under National Health Mission and National Medical College Network to create hubs at medical colleges. They were also being linked with Ayushman Bharat to improve clinical care coordination. This thoughtful implementation across the country can help kickstart Tele-consultation services at a pan-India level.

Telemedicine Society of India

Though the Telemedicine Practice Guidelines mandate training for doctors, the country’s medical fraternity is yet to develop a standardised course or curriculum for capacity building of doctors. In furtherance of this goal, it is recommended that courses must be designed and developed to train medical staff in undertaking successful teleconsultations. In this respect, the Telemedicine Society of India (TSI), a society established in 2001, has come out with its flagship “Train to Practice Telemedicine” course in pursuance of the Telemedicine Practice Guidelines. The course is to bridge the gap by making telemedicine accessible and affordable to those who are willing to provide healthcare which brings them closer to their patient’s door step at invisible costs.

The society, though a self regulated one, is manned by doctors, lawyers, and professionals working in the health sector. Using a specialised society, such as the TSI to run courses, training and oversight of quality hand holding to doctors, nurses and allied staff for telemedicine can be explored in the future.

Conclusion

India reported a 500% increase in tele-consultation for availing healthcare service between March - May, 2020. This rise in online consultations is buttressed by the Government’s support to increasing tele-health services in the country. The working paper has aimed to critically examine the prevailing policies and implementation models giving impetus to tele-consultation. The authors have attempted to make recommendations which enhance the viability of these policies and models. The impetus on tele-consultation is an opportunity arising from the adversities posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. With sound policies, greater focus on promoting a safe digital environment and multi-stakeholder training and awareness, the country can embark on a new phase of Digital Health.

Annexure: Direct and Assistive Government Policies impacting telemedicine and teleconsultation

Meet The Thought Leaders

Shatakshi Sharma is a public policy advisor, has been a management consultant with BCG and is Co- Founder of Global Governance Initiative with national facilitation of award- Economic Times The Most Promising Women Leader Award, 2021 and Linkedin Top Voice, 2021. Prior to graduate school at ISB, she was Strategic Advisor with the Government of India where she drove good governance initiatives. She was also felicitated with a National Young Achiever Award for Nation Building. She is a part time blogger on her famous series-MBA in 2 minutes.

Naman Shrivastava is the Co-Founder of Global Governance Initiative. He has previously worked as a Strategy Consultant in the Government of India and is working at the United Nations - Office of Internal Oversight Services. Naman is also a recipient of the prestigious Harry Ratliffe Memorial Prize - awarded by the Fletcher Alumni of Color Executive Board. He has been part of speaking engagements at International forums such as the World Economic Forum, UN South-South Cooperation etc. His experience has been at the intersection of Management Consulting, Political Consulting, and Social entrepreneurship

Aashi Agarwal is a mentor at GGI and is currently working as a consultant at Kearney. She exhibits keen interest in the social sector and has gained vivid experiences being a part of Teach for India, Katalyst and BloodConnect Foundation. Aashi pursued her B.Tech from IIT Delhi and was conferred with the prestigious Director’s Gold Medal for her excellent all-rounder performance and leadership skills. Outside of work, you can find her writing poetry Slam, learning French or exploring new places, food, lifestyle and culture.

Meet The Authors (GGI Fellows)

Maya Roy is an alumnus of Indian School of Business and Azim Premji University, Bangalore. She has worked for 5 years in the area of Urban Development with various state governments and in Ed tech space (Unacademy). She is currently working at Ernst and Young as a consultant to the Department of Promotion of Industries and Internal Trade, MP

Vallabi is pursuing her integrated masters in development studies from IIT Madras. She has worked as a policy intern at various realms with Government authorities, consultancies and policy think tanks in the fields of inclusive finance, gender, migration, education and rural development. She heads one of the projects of Enactus IIT Madras Chapter. She is currently associated with Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI) in devising policies for women’s financial inclusion in developing economies. She loves cooking and is a local history enthusiast.

Shyam is a fourth-year student at Indian Institute of Technology, Madras. He is currently the Core of Student Relations Team of Saarang 2022. Shyam has a deep concern for the environment and is a great supporter of renewable energy technologies. An aspiring civil servant, he wishes to implement socially relevant technologies in various fields and parts of India. He got introduced to the public policy sector during a group excursion to Delhi, where he interacted with economists, politicians, academicians, and consultants. Moreover, he loves teaching and has been actively involved in tutoring school students.

Sanskruti Vidhate is currently in her first year of Master's in Public Policy from IIT Delhi. She started working in the development sector after completing Electrical & Electronics engineering at VIT, Vellore. She first joined the Teach For India Fellowship in Pune and then worked in 2 social enterprises at a rural community based organisation (CBO) called Social Work & Research Centre (SWRC), Barefoot College in Tilonia village, Ajmer.

Kalash is a fourth-year student at the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras. He is currently the President at ShARE IITM, a student-run leadership and management consulting chapter. At ShARE he has worked on projects concerned with livelihoods improvement and carbon zero mobility. He has also worked as a Business Development intern at CyGenica a biotech start-up and as a B.R.E.W intern at Ab Inbev. An avid fitness enthusiast and a swimmer, he is currently the captain of the Aquatics team of IIT Madras.

Avani Kaushal is a Gold Medallist and alumnus of Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia. She is a former LAMP Fellow and currently practices law in Delhi. She enjoys watching movies and closely follows the Indian stand up comedy space.

Ashima Gulati is a fellow at Teach for India. Prior to joining Teach for India, Ashima has worked as a securities and capital markets lawyer in Mumbai for 3 years. She is also a co-founder of a not for profit organisation that works for COVID-19 vaccination in India. Apart from work, she enjoys painting.

If you are interested to apply to GGI Impact Fellowship, you can access our application link here.

References

4. https://main.mohfw.gov.in/Organisation/departments-health-and-family-welfare/e-Health-Telemedicine

13. https://the-ken.com/story/esanjeevani-the-government-owned-dark-horse-in-indias-telemedicine-race/

18. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18523705/

留言